Behind the Scenes: Scenic and Costume Design for Berlin

The design of Berlin – the world premiere adaptation by Mickle Maher, based on the graphic novel by Jason Lutes, and directed by Charles Newell – is astonishingly singular. The sets and costumes conjure places, people, and themes both specific and universal; move the story at breakneck speed; and create reverberations between our past, our present, and our future.

Below, Scenic Designer John Culbert and Costume Designer Jacqueline Firkins shed light on their processes and inspiration, and how they brought this acclaimed graphic novel to life.

Scenic Design

John Culbert: The story that we were telling includes a procedure or hearing, so—to start—I researched different hearings through history and found that people formally sitting around a table was a constant throughout time. I also researched images of everyday Berlin from the period of the play. There were images of different aspects of life: people in clubs, people speaking in the street, newspaper stands, and the military. These images showed what life was really like at that time.

Then I found images related to the symbolic gestures and themes that repeated throughout the script—energy, traffic, the river. In that same vein, architecturally, bridges and train stations were themes throughout the script.

Train stations played a literal role in this story, but they also represented the idea of a journey: each character was on a journey in this river, and there was movement through space and time. I used exploration models to develop the thinking using these themes. I shared those visual gestures with the whole team for input. During this process, we were also talking about—and learning about—how we were going to tell this story. When we looked at the story literally, there were over 30 scene locations in the script, but we came to the conclusion that the specific location wasn’t critical to the storytelling. The critical dimension was to understand, when these people were speaking, was it intimate? Was it public? Was it private?

The central idea behind the design was: How would we enable the storytelling while it traveled to these different places, and even overlapped with multiple locations at once? We discovered that movement and sound were going to be incredible parts of this journey, and the nature of the movement told us that we would be excited by a big open space with flexibility. We decided to employ tables and chairs that could be moved around easily, so the stage became a flexible dance space rather than a literal theatrical representation.

This led us to think about how we were representing Berlin on stage. We were creating the environment to tell a story that was set in Berlin, but a theatrically symbolic, rather than literal, representation would best serve our story.

Above is a picture of the model, and you can see large arches in the back. Those arches are from a Berlin train station, but they’re painted black, like the back wall of the theatre, and through the arches, we actually see the back wall of the theatre. So when you walk in, you might get the idea that we are in the theatre: Is that the back wall? Is it not the back wall? In addition, you’ll see lighting booms on the side, which—again—allude to the theatricality of how we’re telling the story.

We’re not hiding anything. This is a theatrical journey that we’re going on, and we want the audience to be clear on that from the beginning.

Costume Design

Jacqueline Firkins: We started, of course, with Lutes’s original work; though in a graphic novel, each character needs to be distinct from their chest to the top of their head. That’s what’s often visible in a frame. Onstage, we nearly always see the full figure. We also have a different use of language, which is spoken rather than printed, adding the individuality of each actor to the characterization. So we have very different tools to work with. This production isn’t just a translation or imitation of the graphic novel. It’s unique in its form, in its liveness, in its use of an ensemble and simultaneity of action, and in some of the themes it explores, such as the systematized, collective examination of history Maher braids into his script.

Some costumes in the show closely resemble what’s in Lutes’s drawings. In other places, his drawings didn’t serve us that well, such as where the clothes might not move the way we needed them to or support an onstage costume change embedded in the script. But we did try to honor Lutes’s vision and the incredible work he put into his graphic novel.

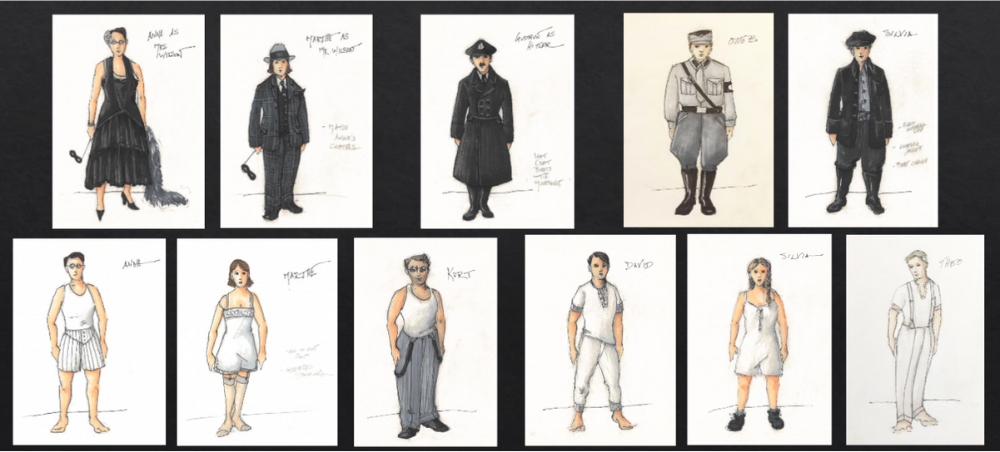

As you saw in the set, the environment has a stripped-out sense of color, which reflects the graphic novel and also abstracts the idea of urbanity. We ran with that in the costumes, bringing them all into grayscale, which gives a clue to the audience: Don’t expect every last bit of detail. Don’t expect every grain of dirt. We’re in a world where things may happen onstage that don’t happen in real life. Somebody may switch characters without warning, or three scenes may happen at the same time. The visual abstraction sets the audience’s expectations for what’s to come and also allows the cast to function as both individuals and an ensemble. They’re the river, they’re the city, and, at a moment’s notice, they become a specific character.

Once we lose color, our other tools become more important, such as weight, texture, and tonal variation. We wanted to play with what absorbs or reflects light, and what feels hard or soft, making the most of working in a tangible language, rather than on paper, and embodying the unique liveness of theatre. With tone, aside from the character of Theo Müller, everybody has an overcoat, which are in our darkest tones. When we strip clothes away, the garments get lighter. There’s so much about intimacy in this play, and many types of intimacy. We wanted the clothes to support those themes, so when characters strip away a sense of darkness, a shield, a kind of armor, they’re wearing something that might feel more hopeful, vulnerable, or innocent.

We also discussed whether we wanted the costumes to feel like costumes, or to feel more like clothes. We landed pretty quickly at clothes, so a lot of my research for this piece was personal or documentary photos of ordinary people, not high fashion. Garments might not fit perfectly, or go together perfectly, but they’re authentic to each character. They move. They have texture and grit. And they’re tactile, allowing the audience to feel like they’re watching real people with real struggles. Though “real” is always a strange word to use when talking about theatre, because what’s real and what’s theatrical? Isn’t everything we do in the theatre always both?

If I did my job well, the costumes will help establish who the main characters are, and they’ll also support the play’s symbols and metaphors. We’ll follow specific character journeys, while also following the journey of the city and the journey of the big ideas Lutes and Maher are exploring in their texts. It’s a lot to ask of a coat or a hat, but if it’s the right coat or hat…