Behind the Scenes: Scenic and Costume Design of THE ISLAND

As part of his creative process, Athol Fugard – one of the co-creators of The Island, alongside John Kani and Winston Ntshona – found inspiration from Polish theorist Jerzy Grotowski. Grotowski was a firm believer that “theatre [should be] stripped of ‘nonessentials’ (costumes, props lights, musics, even the playwright)…and left with the one absolutely necessary element: the living actor in [face]-to-face communion with the spectator.”

This notion could be considered one of the foundational tenets of devised theatre and – perhaps most importantly – one of the foundational tenets of The Island. As we re-create (rather than re-stage) this production for our own audiences, Costume Designer Raquel Adorno and Scenic Designer Yeaji Kim adopt a similar approach, favoring simplicity; symbolism; and design elements that are gestural, atmospheric, and functional.

Check out this behind-the-scenes look at Raquel and Yeaji’s designs, the history, and the cultural context transporting audiences to The Island.

Costume Design

Raquel: Growing up in the 1980s, when Apartheid was still around, and then in the 90s, as it was being abolished, I spent my Sunday mornings watching the news on PBS with my dad; my father was an activist and educator who followed the world news closely. He never shielded me from the horrors of the news.

Quite the contrary, he taught me that the only way to change the world was to open your eyes and see what was happening around you. He taught me not to look away from what made me uncomfortable and – as a direct result of that exposure – I used photography, documentaries, news reports, and articles from South Africa during Apartheid as the inspiration for the design of The Island.

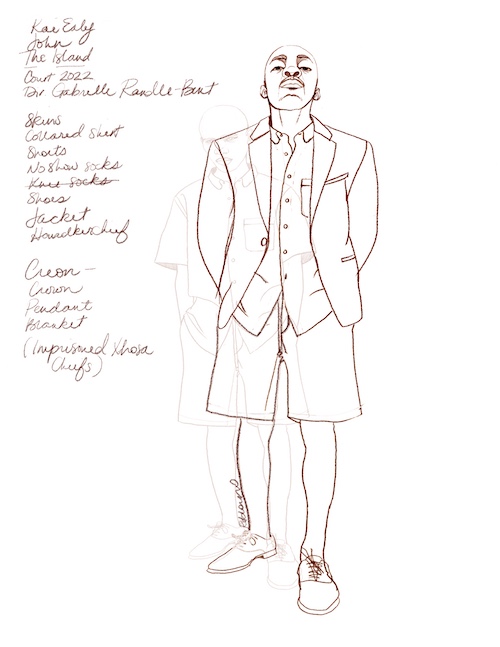

Gabby: And these photos were so interesting. For example, throughout most of Nelson Mandela’s sentence on Robben Island, prisoners had to wear shorts. South Africa is a part of both the Afrikaner and Dutch-German tradition, but it’s also part of the English tradition, and so – in a very European way – shorts are what children wear. For many years, any photo of any of the prisoners, especially images of Nelson Mandela, never showed the prisoners’ legs because the Apartheid government knew that there would be violence in the streets if people knew that these prisoners were being degraded and debased as boys.

Raquel: Right, exactly. We spent a lot of time looking at photos of Nelson Mandela during his time there, and documentary footage depicting the stories of other prisoners. Looking at these source images was hugely helpful, and we hope to recreate these uniforms as accurately as possible, while taking some liberties with color and fabrics to accommodate the athleticism of this production and overall mise en scène.

An important part of this play is John and Winston’s production of Antigone, so that adds an additional layer to the costuming decisions. What does John’s Creon look like? What does Winston’s Antigone wear? What would these two men have access to that they could fashion into costumes? How would the history of this land inform what a ruler looks like, and what a princess might look like?

As part of my research process, I watched quite a few documentaries about Robben Island, and the imprisonment and deaths of the Xhosa chiefs haunted me.

Gabby: For context, Robben Island – throughout history, but especially during colonial history – was many different things. It was a leper colony, and it also was the prisoner of war camp for Xhosa chiefs who fought the settler invaders. So, as Raquel says, our attempt to speak to that history is represented in the costuming of John and Winston’s Antigone and Creon. Antigone’s their approximation of what royalty looks like. What I love about Raquel’s designs – and just how thoughtful she is, when approaching dramaturgy in general – is that, when John and Winston perform Antigone at the end of the play, their version of royalty is not Greek royalty and it’s not European royalty. It is Xhosa royalty. They use their blankets, they use their cups, and they transform the bits of rags in mopheads into a Xhosa princess and a Xhosa chief, rather than how we might imagine a princess and king. And by doing so, we’re put us in conversation with the folks who have been imprisoned on that island before we meet John and Winston.

Raquel: That’s the goal for the designs of Antigone and for Creon: evoke this persecuted royalty as a sign of both remembrance and respect.

Scenic Design

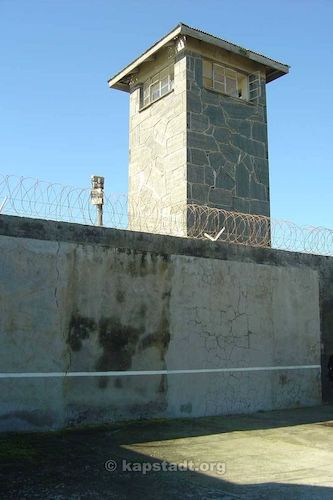

Yeaji: When Gabby and I discuss this production, she always stresses that it’s not a prison play. It’s not about the prison. It’s about the relationship between these two characters; the love and care. So, to highlight that bond, we wanted to create a room where you watch them – their movement, their actions, and their words – rather than a literal depiction of a cell on Robben Island. We were looking to create something that conveyed the sense that these two men are at the edge of the world, they’re totally isolated.

When you research photos of Robben Island, you’ll see it’s a flat island. It’s quiet and peaceful, in its own way, but escape is impossible because of the currents and sea turmoil. So, in our set, we made sure the walls aren’t incredibly high because the walls aren’t the only barrier. We wanted everything to be more simplistic, more gestural. The whole stage is the island, so to speak, and there’s a wall in the back with a window opening. The wall represents Apartheid and racism, generally speaking, and the window gives a sense of what’s beyond this island, the future, but it’s small – there’s no hope. It’s despair.

The labor is really the central action in this play. Prisoners had to work in the quarry for years and years – it’s incredibly tiresome – so labor is a really important element to this show and the design. We have a joke, actually, that it’s the third character in the show. This giant slab is our focal point and, depending on how it tilts (forward or backwards), it can become a burden or it can give you agency.

When the audience walks in and sees the stone slab, it’ll be in a flat position like a table. That’s the representation of the cell. Around the cell, outside and around, represents what they do: the outdoor labor with the sand.

When we go back inside the prison, in the scene transitions, the slab will be tilting backwards to give a roof and we’ll return to the sense of the physical cell. In the later part of the production, when John and Winston put on Antigone, the stone slab will tilt so they can lean against it; this is an opportunity to show their agency in portraying the characters of Creon and Antigone.

And finally, at the end, we’ll go back to the flat position where we started the show. Throughout the rehearsal process, we’re going to play and use movement to explore how the central action can interact with this mechanism.

I’m super excited, and I’m looking forward to what we’ll create together.

Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Ntshona’s The Island is on stage at Court Theatre from November 11 – December 4, 2022 → Get Tickets.

Source: Berner, Robert L. “Athol Fugard and the Theatre of Improvisation.” Books Abroad 50, no. 1 (1976): 81–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/40130109.