The Study is The Struggle, The Struggle is The Study

Kwame Ture, who many knew as Stokely Carmichael, functions in the popular memory of the Black Freedom Movement as a larger-than-life racial icon abstracted from the local people, global communities, and grassroots organizations that made him one of the key political and intellectual figures of the twentieth century. As a racial icon, Ture’s life defies conventional narratives of the Black past and confronts simplistic progress narratives of a nation that both denigrates and venerates Black life. As an organizer, Ture’s legacy remains a potent source of radical transformation and reinvention for Black youth who still consume his charismatic college campus speeches on YouTube in the twenty-first century. How to critically understand the Blackness of such a complex human in the face of a concerted effort to malign and misremember him is the work of artists, academics, organizers, and— importantly—the community of unnamed footsoldiers getting ready for revolution through ongoing study and struggle.

A new play chronicling Kwame Ture’s life—Stokely: The Unfinished Revolution, by Nambi E. Kelley— joins this chorus of creative cultural production. In the play, Kelley positions Ture in relation to other well-known icons of the Black Freedom Movement: James Baldwin, Fannie Lou Hamer, Malcolm X, Ella Baker, and Diane Nash, among many others. However, the central lens through which the audience reads Ture’s humanity and mortality is through the care of his mother, Mabel Florence Charles Carmichael, as he struggles with terminal cancer and records memories of a lifelong commitment to revolutionary struggle. Kelley skillfully provides pivotal glimpses into the evolution of a man moved by social movements—a man with a distinct gift of moving others to transcend themselves in the face of real fear of death—as he grapples with his own imminent transition in Conakry, Guinea.

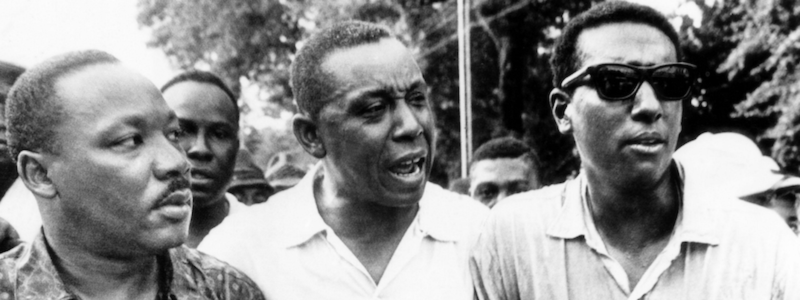

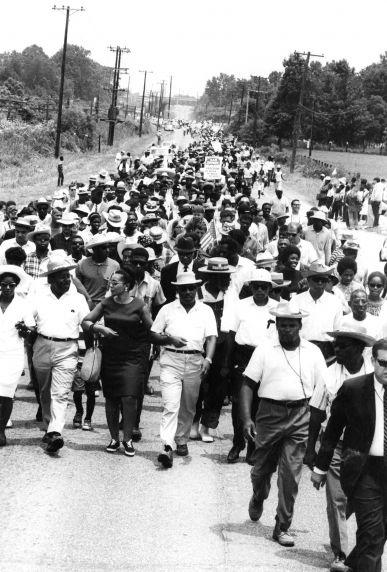

In a powerful 1966 speech in Chicago, Ture implored the audience to “study Black history, but don’t get fooled,” recognizing the dangerous misrepresentation of Black life and politics which remains a problem today as it was then sixty years ago. Indeed, Ture is the individual most often associated with the late 1960s’ turn toward a politics of Black Power, frequently misunderstood through false binaries of violence/non-violence, civil rights/self-determination, and integration/ separatism. These false choices fool the public through individualism, inclusion, and celebrity worship and narrow the scope of freedom dreams conjured by everyday Black people struggling to forge a decent life in a fundamentally racist society. As Ella Baker said of Martin Luther King Jr., it is “the movement that made Martin, not Martin who made the movement.” The same applies to Kwame Ture; his vision of Black Power emerges from grassroots struggle with native Mississippians such as Mukasa Dada (Willie Ricks), who first coined the phrase “Black Power” alongside Ture during the June 1966 March Against Fear.

From the Caribbean island of Trinidad where he was born in 1941, to his youth and adolescence as a Black immigrant in 1950s New York City, to his radicalization at Howard University as a student activist in NAG (Nonviolent Action Group) and his organizing work with the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the 1960s, Ture confronted fear directly and always in, and for, community. Grounding Ture’s early life in these contexts is important for the play and, more broadly, for understanding the phalanx of committed Black youth organizers alongside whom he frequently put his life on the line. Though Ture became chairman of SNCC in 1966, his Howard roommate (and fellow NAG and SNCC comrade) Cleveland Sellers is quick to point out that “SNCC” and “leadership” were not always terms that went together. Instead, Sellers argues that “when we talk about leadership, we talk about it in the context of his ability to organize” young and old, college students and rural Black native Southerners in Mississippi and Alabama, all united against domestic, legalized systems of white supremacy and imperialism abroad in the U.S. Vietnam War. In this way, the play works to dismantle what SNCC veteran Julian Bond termed the “Master Narrative” of the civil rights movement that takes a top-down approach and focuses on individual charismatic leadership specifically eschewed by this Black youth organization committed to a radical participatory democracy.

The late 1960s’ globalization of the Black Freedom Movement is reflected in the evolution from Stokely Carmichael to Kwame Ture, from a national demand for Black Power to a global Pan-Africanism capable of uniting diverse religious, linguistic, and ethnic peoples racialized as Black. The dismantling of Jim Crow segregation could no longer be viewed as separate from anti-colonial movements for African independence in Ghana and Guinea. As such, it was through the influence of figures like Kwame Nkrumah and Sékou Touré that Stokely Carmichael would evolve as the co-founder and president of the All African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP). This global vision and evolution of Ture’s grassroots organizing are essential to understanding the context of his charisma, humor, fearlessness, and commitment to an unfinished revolution.

What does it mean to be “ready for revolution,” which is both the title of Kwame Ture’s autobiography and a salutation through which he was known and sought to know others? Performances begin on May 24th, one day before African Liberation Day (celebrated annually on May 25th) which the A-APRP commemorates as “a day to reaffirm our commitment to Pan-Africanism, the total liberation and unification of Africa under scientific socialism.” Like African Liberation Day, the play is both a memorial and a commemoration: of the evolution from Stokely Carmichael to Kwame Ture; and the women, communities, and politics that shaped him. To be ready for revolution is to understand theatre and art as a lens through which we struggle to study —and study to struggle—Black history, Black life, and Black liberation.

Dr. Theodore Foster will be participating in the Agora conversation about Stokely: The Unfinished Revolution as part of the Black Power Series. The Agora will be on May 23, and Stokely runs May 24 – June 16. Tickets to both events are available online or by calling the Box Office at (773) 753-4472.

Dr. Theodore Foster III, PhD is a Black Studies scholar specializing in the production of historical memories of the modern civil rights movement, Black visual culture, and neoliberalism within Black political thought. His research focuses on how memorials, commemorations, activists, politicians, and artists visualize and narrate the history of the 1960s Black Freedom Movement through divergent political lenses. His book project is titled The Firehose Next Time: Civil Rights Memory, Neoliberalism, and Black Visual Culture. Dr. Foster is an Assistant Professor of African American History and Black Studies at University of Louisiana at Lafayette.