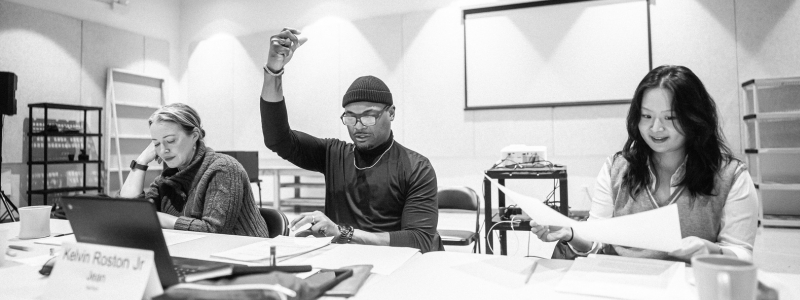

In Conversation: Actors Mi Kang, Kelvin Roston Jr., and Rebecca Spence

Played out in real time with only three characters, Miss Julie is deceptively simple, but its depth, honesty, beauty, and brutality are astonishing. Since its premiere in 1889, it has remained both incredibly popular and incredibly complicated. To some, it’s a thorny portrayal of a power imbalance written by an avowed misogynist. To others, it’s one of the greatest—if not the greatest—works of realism onstage.

Mi Kang plays Julie, an aristocratic woman desperate to escape the trappings of her status; Kelvin Roston Jr. plays Jean, Julie’s valet who’s willing to do whatever it takes to ascend beyond his station; and Rebecca Spence plays Kristine, Julie’s cook and Jean’s fiancée, who refuses to upset the status quo. Associate Director of Marketing Camille Oswald recently spoke with these three actors to reflect on these iconic roles and what it means to stage this production in this moment. Their takeaway? Everyone’s playing with fire.

Below is an excerpt of their conversation.

What is the biggest challenge/thrill of playing each of these characters?

Rebecca: Kristine represents the establishment, the class order. She’s certainly a woman who has opinions, and her own conflicts, and certainly her own thoughts about Jean and Julie, but in the subtlety of her quietness, she represents the negative space. On the page, in terms of dialogue, there’s not a ton to work with, but [her language is] so filled with her understanding of the system, her acceptance of it, her judgment of herself within that system, and her judgment of the other two characters who are trying so hard to rally against it.

Mi: The biggest thrill [of playing Julie] is that she’s a full character—she is so emotionally open and available, and I’m excited to get into her grit. That’s also the biggest challenge. How do you play this massive character with all the different layers of her humanity? How do you do this without being shallow or one-note? How do you remain honest to who she is, and who she is in relationship to the world around her, and the people around her, as well?

Kelvin: The biggest thrill is getting the opportunity to do a three-hander with these amazing women here. I’ve worked with Rebecca in a film, but this will be our first time onstage together, and I’ve been waiting for this. That’s a thrill.

It is, of course, a thrill getting to sink my teeth into this character. The biggest challenge is juggling the class system, without judging [Jean] or his narcissism. I feel that he knows that he deserves [more], and should be higher than the station that he’s in, but he has to quelch those moments where he wants to speak freely as the person he thinks he should be. That, on top of whatever misguided attraction he has to Julie; how to walk that tightrope of whether it’s truly desire, or if it’s just something he feels that he deserves and maybe would have, if he weren’t born into the station he was born into. Working that class system when it does not agree with what your brain says about you, trying to walk that tightrope.

The want in this play feels so bare, and so apparent, and so raw. The whole play is just pulsing with want: I want more, I want different, and I’ll do whatever it takes to get there. With these competing wants in mind, how are these characters foils for one another?

Kelvin: Kristine always reminds Jean of his station, and I think she helps him feel what love really is, as opposed to what he might think he feels for Julie or that confusion of emotion he has with Julie, even though he doesn’t necessarily know how to label it. Julie also reminds Jean of his station, but it’s very different. Julie holds the mirror up to Jean so he can really see the deficiencies in himself. Jean is a lesson in trying to strive for more, but [through him], you can also see that there are many, many better ways to attempt ascension.

Mi: These characters are all very different, but also very similar. In the eyes of Julie, Kristine is a very stable character; she has her faith (which Julie is envious of). Jean represents an out for her, but I don’t yet know what that out is, exactly; as Julie, [something] happens to me [in the play], and it’s negative, and I’m in fear, and so I possibly glamorize this other life for Jean, and me, and Kristine, and [fixate] on this notion that we have to leave. At this moment, right now, I don’t know if Julie even believes that. It’s nice to have these dreams, the belief that we could do this, but ultimately, I don’t actually know if she can put her money where her mouth is. She learns a lot from these two people. I’m specifically thinking about the moment where Kristine tells her about faith, and who that’s for, and who will go to heaven, and who won’t, and how, after Kristine leaves, Julie says, “Well, if what Kristine says is true, then she’s also not going to get into heaven.” She’s learning in real time, and the people teaching her are Jean and Kristine.

Rebecca: It’s such a polarizing play. I said yes to this project because I think [Director Gabrielle Randle-Bent] is a genius, and her vision for any play she does is so deeply rooted in her phenomenal research and the insight that she brings, but when I read it in college, I was like, “Oh my god. Strindberg is a misogynist, and what a bleak view he has of women; he sees them as either the saint or the whore. How are we going to do this?”

A podcast I listen to researched the production history, and there has been a production of Miss Julie somewhere on the planet every single year since it premiered in 1889, so why do we keep coming back to this play? I spoke to Gabby, and something she said was that our country, specifically now, has gotten very, very comfortable talking about race and talking about gender issues, but we have never fully tackled class. Given where we are now with this huge surge towards democratic socialism, even in progressive parties, we still can’t deal with actual class issues: talking about that yearning to rise, or—in the case of the people who have risen—their guilt about it and how they utilize the privilege at their fingertips.

Kristine is this steady, bordered line that goes through the action—she is the system that’s pushing it through. She’s the least bothered of the three of them about their state; there’s freedom in being like, “I know my boundary here, and I know my boundary here, and I can live freely in between.” She represents the pragmatic counterpart to these two—Jean, who’s below the level they think they should be at, someone trying to ascend and go higher; and then Julie, someone of really high status who’s deeply lonely, and deeply forgotten, and is trying to find her people, trying to find relevance, and trying to say, “I’m simple, I’m simple, I’m simple—until I’m not.” Kristine is just the steady throughline of who lives within those rigid boundaries.

Kelvin: Thinking about the three, Kristine is technically the only one who lives in any type of freedom. [Julie and Jean] wear this chip [on their shoulder] every day. They drag this weight, and then retreat into what’s comfortable. Julie wants to escape, but she still has the advantage of her privilege. Jean wants to ascend, but knows that if things hit the fan, he can still disappear back into his position. There’s a tug-of-war happening within each of them.

What contemporary conversations does this production join or challenge?

Mi: The wealth disparity in this country continues to grow, and the media that I’ve been consuming lately about Asian Americans is one of wealth, right? You have the movie Crazy Rich Asians, there’s the Korean movie Parasite, and there are conversations about East Asians and class. My observations have been that they’re in the upper class, or they’re associated with wealth, or at the very least, they’re comfortable. We have the stereotypes of East Asians being in the medical field, or lawyers, and automatically, those careers imply a certain level of money. But I don’t come from a wealthy background. [My family] immigrated. I have a very stereotypical immigrant story. Seeing these stories about Asian people associated with wealth, and [knowing] that’s just a completely different experience from what I had… I’m still trying to grapple with that. Even as an actor, even with its privileges, my career is very in flux. It’s very up and down. It’s never stable. To now portray a character who doesn’t have to think about money, who has everything she needs, or can get whatever she needs by purchasing it, but wants something that she cannot buy with money—that’s interesting.

Rebecca: The great thing about theatre is that it’s a living text, so we can breathe new intention [into the script using the original words]. There’s so much force and attention focused on who we allow to ascend, particularly now, with ICE and immigration issues; these rigid boundaries are so magnified. There are billionaires and the upper percentage of earners who’re just getting wealthier, and wealthier, and wealthier, and who are changing the rules as we speak. Then there’s this middle ground of people, like Kristine, who’re like, “I don’t like that, but I’m good right where I am—it doesn’t affect me,” but that level of comfort can end up being very dangerous. If we’re making parallels, it’s Kristine who’s the most dangerous at the end, who prevents either one of them from leaving. The establishment is still winning, and—for some—there’s comfort in that.

Mi: There can also be an element of survival, right? “If I just stay in my lane, and keep my head down, and don’t say much, and don’t disrupt anything, I’ll make it out of here alive and so will my loved ones.”

How would you describe Miss Julie in three words? Or even more challenging, to match the title of the play, two words?

Kelvin: Intense. Thought-provoking.

Mi: Complicated. And quite straightforward. All of these things are in play, and their wants are very clear. If we stay true to that want, the complication comes with us.

Rebecca: In this adaptation of the play, there’s a line about how the characters are “playing with fire.” And that’s what this is. Everyone’s playing with fire.