The Science of Strindberg: A Personal Essay

Early on in the process for Miss Julie, I sent [Director Gabrielle Randle-Bent] a text that simply read:

“Did you know that Strindberg used to inject apples with morphine to see if they had nervous systems…”

It feels like an artist is always navigating a relationship between their constitution, their inherited traits and acquired tastes, and the contexts of the world they live in. Maybe that’s inherently what living, in general, is—but artists channel that relationship between context and constitution through the lens of curiosity, of questioning. In Strindberg, I find that there is an unquenchable, and maybe even cursed, curiosity that plagues him.

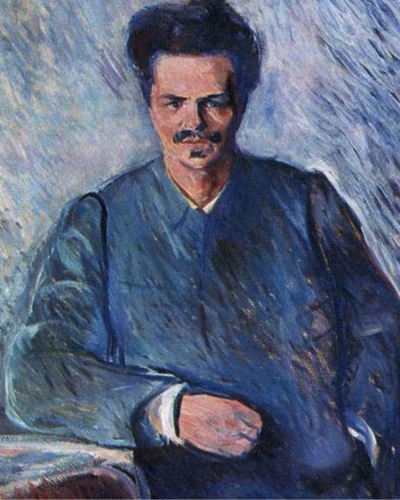

When you look at the extensive sweep of his life’s work, you start to see a sprawling portrait of a man using any and every tool in his arsenal to sate that curiosity. He was painting, writing historical fiction and dramas, creating his own cameras to capture the night sky, penning multiple autobiographies, experimenting with transmutation and alchemy. The sheer enormity of his creative output felt compulsive, almost clinically so—he wrote Miss Julie in the span of only two weeks. Miss Julie, a play heralded, in many senses, as the apotheosis of naturalism—a movement fascinated by the ways human life is subject to the uncontrollable forces of nature.

One day, I turned to Gabby and said,

“Miss Julie reads like a science experiment to me.”

In Miss Julie, I see a central question,

“Can we transcend our position (class, gender, race, etc.)?”

Or a hypothesis:

“If we succeed in transcending our position, then something is created and something is destroyed.”

With this hypothesis in hand, Strindberg picks his subjects. Two variables, and a constant. Miss Julie and Jean, variables who are interested in directional movement between their positions, and Kristine, the constant, who appreciates, finds value, and has a need for a structured class system. Then the experiment begins.

“On a night like this we’re all just ordinary people having fun, so we’ll forget about rank. Now, take my arm!” – Miss Julie

It’s no accident that the environment chosen for this experiment is Midsummer, the longest day of the year, the summer solstice, a night when anything can happen. With origins rooted in ancient pagan rituals to celebrate fertility and abundant harvests, the significance of the festival, of a rite of passage, of ritual where people are often between social roles serves as an essential boon to the play and what Victor Turner would 80 years later call “Communitas,” an intense feeling of fellowship, a moment where structured social ranks collapse and there is a sense of perceived equality. Communitas can only occur in liminality, the threshold where something has been destroyed but something new has yet to be created, a space that the characters occupy as soon as Miss Julie enters the play.

Strindberg said of Miss Julie: “In the following drama I have not tried to do anything new—for that cannot be done … but I have chosen, or I have surrendered myself to, a theme that might well be said to lie outside the partisan strife of the day: for the problem of social ascendancy or decline, of higher or lower, of better or worse, of men or women, is, has been, and will be of lasting interest.”

He knew that these themes would transcend the time and place in which the play was written. Instead of seeing Miss Julie as a naturalist drama, the scientific method holds the key to its timelessness. A hypothesis, variables, observation, and experimentation. Questions about the world we live in that can only be answered when those variables are brought together to the point of combustion.