The Erotic as Power

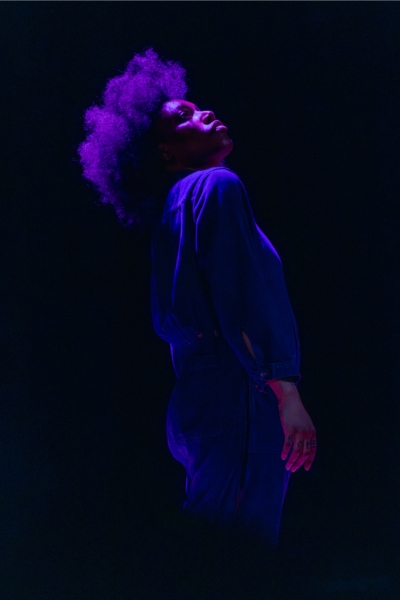

Director of Engagement Kamilah Rashied recently sat down with dancer, burlesque performer, and performance artist Jenn Freeman—who also performs under the name Po’Chop—to explore Audre Lorde’s 1978 essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” and its influence on Freeman’s work. In their conversation, the two reflected on Freeman’s life, art, worldview, and Freeman’s most recent project THICK: a crumbling freak show.

In “Uses of the Erotic,” Lorde argues that suppressing the erotic in women’s lives—and narrowing it solely to the pornographic—is the product of a Western, male-dominated view, a calculated social conditioning to corrupt the source of women’s power to keep them from assuming it fully. She goes on to reclaim the original Greek meaning of the word’s etymology, eros—the personification of love, creative power, and harmony—and concludes that the erotic is the life force itself, a deeply felt non-rational, sensual energy that exists in every aspect of our lives when we assume our right to be fully liberated.

Marti Lyons’s adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew is built upon the same themes of power, control, sensuality, eroticism, and embodiment. This fresh interpretation of Shakespeare’s classic distinctly centers feminine desire. By exploring these ideas, the play—alongside works like THICK: a crumbling freak show—engages a larger conversation about women’s agency and the erotic as a catalyst for fulfillment and empowerment.

Kamilah: How did your relationship with the works of Audre Lorde begin?

Jenn: It began with the poem, A Litany for Survival. I found, or somebody gave me a copy, because I was going through my Saturn return (a significant astrological period when the planet Saturn returns to the same position it occupied at your birth, typically occurring around ages 27-30 and again in your late 50s, ushering in a period of self-reflection, often leading to major life changes). There was no grounding, no nothing. I felt like I was just falling, and spiraling, and I came upon that poem, and it became my prayer. I just started waking up every morning and reading the poem out loud. Eventually I had it memorized, so I was just reciting it. From there, it sparked my curiosity about Audre Lorde, so I got a copy of Sister Outsider, and that’s when I read Uses of the Erotic [an essay included in Sister Outsider]. That was 12 years ago.

Kamilah: How did these texts eventually go from things that were holding you personally into things that were cradling your creative work? I’m curious about that transition, how it helped ground you and then worked its way into your artistry.

Jenn: After reading it, I was compelled to read it with other people, so I created reading groups, reading circles, where that was the sole purpose. In a way, it was like a Bible study. Then I [wondered], “If this is like a Bible study, then what would worship services look like, if this is like the sacred text?” So then I created a show called Thank the Lorde, where Uses of the Erotic was the driving sacred text.

Tiff [Beatty—poet, creative collaborator, and Freeman’s partner] created a sermon where Uses of the Erotic was the text, like a benediction, and we devised rituals and wrote poetry in response. Once I did that, I was like, “Oh, maybe there’s more. This is a series of worship services.” I continued that practice of using Lorde’s writing and poetry as the guiding force behind a deeper creative question, and that question was, “How can the erotic be a Holy Spirit?” I was devising movement that sought an answer to that question. Around this period, I was merging these ideas with my personal life. I moved to Bronzeville, and I began thinking about the neighborhood’s history, and Black women and their legacy, which drove me to look for examples of other Black women—specifically in Bronzeville—whose lives and work were connected to the erotic, and that became another worship service.

Kamilah: What did it look like to bring people together in a spiritual practice around Lorde’s work? Where were you convening?

Jenn: The reading groups were happening all over the country. One of the first ones was at Chicago Art Department, but I would teach workshops at burlesque festivals, at gallery spaces, at dance studios. The early worship services for Thank the Lorde were at Steppenwolf as part of their LookOut Series. The most recent one, The People’s Church of the Ghetto, was at Blanc Gallery. Both of these projects—but especially the last one—allowed me to challenge myself, to fully settle into my visual art practice and my space-making practice. Through Lorde and by allowing my creative compass to run wild, I began expanding into installation work, which planted the seeds for House of the Lorde [Freeman’s creative studio and gathering space at Mana Contemporary].

Kamilah: Were you a movement artist first, and then came into burlesque? Or did these two emerge for you at the same time? Did your discovery of Lorde’s writing happen after those practices were already underway? I’m really interested in how those weave together into what I think is one of the most sophisticated performance practices I’ve ever seen.

Jenn: Movement, or dance, came first. My mom would say I was an overactive child, so she took me to the doctor, and the doctor prescribed me Ritalin. She was like, “I’m not going to put my baby on Ritalin, but I will put her in a dance class so she can move and get that energy out.” So she put me in a dance class. I remember the first time I was there, just thinking, “This is incredible. This is what I’m going to do for the rest of my life.”

I started dancing at three or four years old, and most of my adolescence was studio dance and praise dancing in church (which also informed how I think about movement). Then I came to Chicago to study modern dance at Columbia, and I didn’t finish school because of the culture. There was no internet [at the time], so I didn’t really know what I was getting into, and I was heavily Christian. I went to a liberal arts school and had my mind blown, culturally. I came out—or rather, began to figure out my own identity—when I left school, and that was when I started to figure out what I was meant to do. I had a really tough time coming out. I got a job to sustain myself, and I wasn’t really doing anything creative—no arts, no dance, nothing. During this time, I went to a friend’s burlesque show, they had an empty spot, and she put me on to fill it.

I did a few performances and started to think, “I could really do this!” From there, I used burlesque as a tool to work through my relationship to spirituality. Even when I first got into burlesque, even before I found Audre Lorde, I was thinking about how to disrupt it. At that time, there weren’t a lot of Black performers. There definitely weren’t many people who were bringing politics, or something outside of the vintage pin-up aesthetic. I was really interested in disrupting that, presenting femininity in a way that was not demure, not—

Kamilah: Coquetteish. Not Betty Boop.

Jenn: Yeah! So I performed burlesque and drag for about eight years, and then I found Audre Lorde. She affirmed and really amplified—allowed me to amplify—what I was already touching upon, but maybe hadn’t realized that I was doing.

Kamilah: As a person who works with a lot of younger artists and younger professionals, I think it’s so important for people to see that you don’t just wake up in the morning with a fully realized practice. It’s actually a discovery process that’s equal parts practice and study and intention, and serendipity. It can be informed by people who introduce you to something that revolutionizes the way that you think about what you’re doing.

Jenn: A lot of the foundation of my practice came from the connections I made at Columbia College. I wouldn’t know about burlesque if I hadn’t met Jeez Loueez, who I met through Columbia and was the first person I saw perform burlesque who believed in me. I was married when I first started doing burlesque, and I met my spouse at Columbia, too. They taught me a lot; what I know about theatre definitely came from my then-partner, who was a director.

Kamilah: Even though you clearly are a dancer, I think of you as a performance artist. When I see you perform, it’s clear that this is storytelling that only the body can do. Can you talk about the role of the erotic in telling a story, in building a world?

Jenn: When I came upon Uses of the Erotic and sat with how it was going to impact my life, I had to shed everything I knew about dance. I had to let go of all my training, in some ways. While I’m grateful for that training, if I want to tell the narrative I want to, I have to let go of a passe and a pas de burrée and all this stuff that’s been put on me, and I have to really think about how my body wants to move and allow for what I think of as erotic—which is chaotic. It’s not always rational. It doesn’t always have words. It’s not always comfortable or easy to digest. I allow that to sit in my body, and in the spaces that I’m creating with this work.

When I think about worldbuilding, I have a deep desire for people to forget where they are when they’re experiencing my work. I want us to go into this portal where you’re not even focused on if you’re in a theatre, or in a chair, or anything—you’re so in it, that you can slow down time and just experience your senses. I think part of the erotic is an ascent. All your senses are activated; it’s kind of overwhelming. You’re tasting, feeling, smelling—everything is magnetized.

Kamilah: In theatre, that’s called “suspending disbelief,” when you fully absorb into the world that’s being created. You leave yourself.

Jenn: Yeah, you leave yourself, and that’s such a rich space because it’s an opportunity to encourage people to think for themselves; to feel, to experience, and to trust themselves and trust their experience. It’s such a rich [space from which] to teach, to remember.

Kamilah: It’s also a spiritual space, in my opinion, which is why I’m fascinated by the placemaking work and the community-building work that you do around text. It’s so deliberately spiritual.

Jenn: I think [that’s] because I grew up in Christianity. Part of me is trying to create this anti-program to heal from those experiences and cleanse myself on a cellular level so I can have an alternative way of being spiritual and being connected that’s not rooted in Jesus or God. I have a hard time with Christianity, so a lot of my work is, in some ways, an offering to deprogram; another way for me to commune with ancestors, or with the other side. Which is, for sure, another reason why I really cling to Uses of the Erotic! Lorde offers so many ways to reconsider how we view the spiritual world, and its connection to our senses and to sensuality. For me, there’s no separation between the two. They have to be intertwined to really [receive] what life is trying to offer us.

Complementing this production of The Taming of the Shrew, Court Theatre is proud to partner with Jenn Freeman on their next project, THICK: Studies in Refusal. Learn more and reserve tickets here or by calling the Box Office at (773) 753-4472.