Emile Griffith (1938-2013)

Emile Griffith, the greatest welterweight fighter in the history of boxing, was discovered at age sixteen working in a hat factory in Manhattan’s Garment District. Howie Albert, the factory’s owner, recognized an extraordinary talent in his young employee and volunteered in 1956 to launch and manage Emile’s professional career as a fighter. Emile and his mother, Emelda, recent immigrants to New York from the U.S. Virgin Islands, accepted Albert’s offer immediately, believing that boxing would be a path to a better life.

Emile trained tirelessly and enthusiastically, and his career soared. His formidable gifts ultimately made him a six-time champion of the world, and wealthy enough to bring his entire family to the United States from the island of St Thomas, settling them comfortably in a rambling, 10-bedroom mansion in Queens.

Griffith’s astonishing rise coincided with boxing’s popularity as a televised sport; the young fighter proved a natural fit for television. As an athlete, he not only displayed exceptional power and artistry in the ring, but also his exuberant personality, brilliant smile, and irresistible warmth and charm were evident to all. For millions of viewers across the country who regularly tuned in to ABC’s Friday Night Fights, Emile Griffith was a popular and widely admired figure.

Social conventions in the 1960s proscribed public discussions of an athlete’s sexual orientation. At a time when homosexuality was criminalized by the laws of the State of New York, Emile Griffith’s sexual identity was quietly accepted within the tight-knit brotherhood of the boxing community. Emile was known to pursue romantic relationships with both men and women. He invited boyfriends to watch his sparring practices at Gleason’s Gym in the Bronx, and visited gay bars in Manhattan’s Times Square. His phenomenal success as a fighter, and the steady support of his manager, Albert, seemed to protect him from criticism.

Occasionally, sports reporters tacitly acknowledged Emile’s unique status in the boxing world by writing articles about his one creative interest outside the ring: designing ladies’ hats. Yet for every story focusing on Emile’s work in high fashion, his manager released publicity photos of the fighter posed with various women—well-known models and nightclub stars—described as his girlfriends.

Occasionally, sports reporters tacitly acknowledged Emile’s unique status in the boxing world by writing articles about his one creative interest outside the ring: designing ladies’ hats. Yet for every story focusing on Emile’s work in high fashion, his manager released publicity photos of the fighter posed with various women—well-known models and nightclub stars—described as his girlfriends.

The delicate balance between Emile Griffith’s private life and his career as a professional boxer began to shift in 1961, the year he seized the welterweight world championship title from Cuban fighter Benny Paret. Born in a sugar-farming region of central Cuba, Paret left school at age six to work in the cane fields. Unable to read or write, and earning just $2 per day as a cane-cutter, Paret turned to boxing as a route out of grinding poverty. The biggest payday of the his career came when he won the world championship title in 1961 at age 25. Paret was crushed a few months later when Emile Griffith vanquished him in a challenge match and claimed the gold belt as his own.

It was during the fight for the 1962 world welterweight championship title that Emile’s private life suddenly became a public issue. Paret and his manager, Manuel Alfaro, believed they could rattle Griffith and throw him off his game by breaking the code of silence that protected Emile’s identity. In pre-fight interviews with New York sportswriters, Alfaro described Griffith as effeminate and unmanly, calling him unworthy opponent for any boxer—such as Paret—who prided himself on his masculinity.

On March 24, 1962, at the weigh-in before their decisive fight at Madison Square Garden, Paret hurled anti-gay slurs at Emile that were witnessed by members of the press and officials from the New York Boxing Commission. Hours later, in the twelfth round of their match, Emile would trap Benny on the ropes and deliver 23 uppercuts to his head. The match referee, Ruby Goldstein, remained frozen in place, doing nothing to stop the fight. Paret collapsed in the ring and never regained consciousness. He died ten days later in hospital.

Norman Mailer, present that night, wrote his famous essay, “The Death of Benny Paret,” that would become part of a growing body of writings questioning the ethics of boxing as a spectator sport. Though others pointed to the failure of the referee and the extensive head injuries Paret suffered in an earlier fight with middleweight Gene Fullmer, Emile blamed himself. His exuberant personality deserted him, and boxing became almost impossible. Retirement was not an option, however. As he explained to reporters: “I have eight people to support, and no other profession than boxing.”

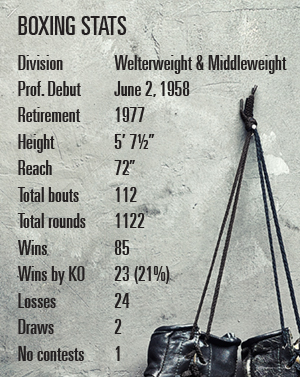

In 1977, Albert urged Emile to quit. After nineteen years in the ring, his shaky hands, fragmenting memory, and slow speech were tokens of greater problems that lie ahead. Emile left the sport knowing no other boxer had fought more championship rounds than he had: not even Sugar Ray Leonard or Muhammad Ali.

Luis Rodrigo, Emile’s partner for over thirty years, became the former world champion’s guide and caregiver, helping Emile stay oriented in time and space as dementia pugilistica increasingly took a toll.

In 2004, friends arranged for Emile to meet and reconcile with Benny Paret, Jr., his former opponent’s son. The encounter was a milestone in Emile’s life, helping him achieve a measure of peace.

In 2012, Puerto Rican fighter Orlando Cruz became the first boxer to publicly announce his homosexuality. Cruz dedicated his first fight as an openly gay athlete to Emile Griffith.

On July 23, 2013, the International Boxing Hall of Fame announced that Emile had died of kidney failure and complications of dementia at an extended-care facility in Hempstead, N.Y.