A Dynasty to Remember

The Lion in Winter is a fictionalized version of how the playwright, James Goldman, imagined the conflicts that created one of the most important English monarchical dynasties—the Plantagenets. The easiest and quickest way to sum up the importance of this line would be to conjure the name of the 2014 best-selling book by Dan Jones that explains their history: The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England.

Although this play is fictional, most of the events surrounding the events are historical. To separate the fact from the fiction, there was no Christmas court in Chinon in 1183. In addition, there are many more mistresses and children attached to Henry II than seen or mentioned in this play. Despite those small things, the facts that become the historical backdrop of the play are just as interesting as the fiction. For example, just ten years prior to the events found in this play, was a revolt—the Revolt of 1173—that changed the family dynamics and led to the fruitful historical playground Goldman used to create this story.

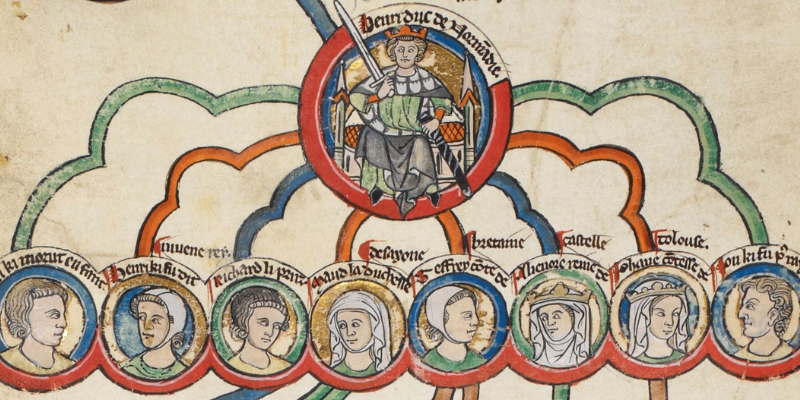

The Revolt of 1173 was a rebellion against King Henry II of England by his sons Henry the Young King (King Henry II’s eldest legitimate son); Richard, Duke of Aquitaine; Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany; and his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine. The revolt began because of King Henry II’s decision to bequeath three castles, which were part of Henry the Young King’s inheritance, to his youngest son, John, as part of the agreement for John’s marriage. The brothers banded together, along with their mother, in an attempt to keep the Young King’s inheritance intact. The revolt went on for 18 months, caused massive amounts of damage, and ultimately failed. The lasting legacy of this revolt was the “imprisonment” of Henry II’s wife, Eleanor, and the need for reconciliation between the three sons and Henry II. This reconciliation did occur. However, it was short-lived and King Henry II was back at war with his father and one of his brothers by 1183.

By Christmas of 1183, when Goldman’s play begins, Henry the Young King has died; he contracted dysentery while pillaging local monasteries to pay his mercenaries for the campaign against his father. The Young King’s untimely death and the lack of resolution (since Henry II thought that the aforementioned reconciliation was a trick) left a void that now exists in the family. The eldest legitimate son is no longer on this earthly plane to inherit the kingdom and Henry II is not convinced that the lands must go to Richard, his second eldest legitimate son. In the end, this play gives a fictionalized account to the historical eventuality that we know—that Richard the Lionheart will succeed this father.

This play is a small snippet of a longer historical legacy: the Magna Carta was signed under King John (the aforementioned youngest son), and both the War of the Roses (which Shakespeare spent many of his history plays documenting) and the Hundred Years War (which was the defeat of this line) all occurred during the reign of this house. This history has inspired many plays and movies, and will probably continue to do so. We invite you to find your own inspiration here, either in King Henry II’s fictional Christmas court or the very real Court Theatre.

The Lion in Winter runs from November 3 – December 3, 2023 and tickets are available now! Subscription packages including this production are also available for purchase online or by calling the Box Office at (773) 753-4472.